Notes on Philosophy

Why philosophize?

"Some people see things that are and ask, 'Why?' Some people dream of things that never were and ask, 'Why not?' Some people have to go to work and don't have time for all that."

~George Carlin

When most folks first experience the philosophers of old, most are too young and inexperienced to fully understand its profound meaning and teachings until way later in life.

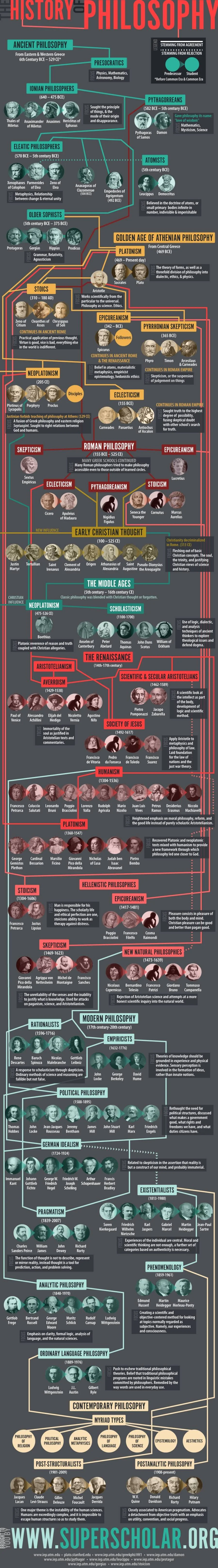

The realm of philosophy has shaped human thought for centuries, challenging assumptions and probing the depths of existence. Throughout history, philosophy has played a pivotal role in shaping our understanding of the world. It has been the driving force behind significant intellectual developments and tackles fundamental questions that lie at the core of human existence.

When we think of philosophy, our minds often turn to the study of prominent philosophers like Plato, Aristotle, Marx, and Nietzsche. However, this limited perception reduces philosophy to a mere academic pursuit, confined to the study of specific thinkers. In reality, philosophy is much more than that – it is the love of wisdom and the exploration of fundamental questions about life, knowledge, existence, and ethics.

If you don't understand the presuppositions of your beliefs, especially in the moral, political and social spheres, you are indubitably an unwitting prisoner of established dogma and the reigning orthodoxy of the world models of your era.

When you start to question the reality that has been programmed into begin to actually form our own beliefs and values, having a road map for the journey that others have undertaken and becoming aware of the obstacles that may emerge is utmost importance.

General common sense anf life experience generally starts out with the assumption that things are as they appear.

Philosophy challenges this assumption.

“The man who has no tincture of philosophy goes through life imprisoned in the prejudices derived from common sense, from the habitual beliefs of his age or his nation, and from convictions which have grown up in his mind without the co-operation or consent of his deliberate reason. To such a man the world tends to become definite, finite, obvious; common objects rouse no questions, and unfamiliar possibilities are contemptuously rejected. Philosophy, though unable to tell us with certainty what is the true answer to the doubts it raises, is able to suggest many possibilities which enlarge our thoughts and free them from the tyranny of custom. Thus, while diminishing our feeling of certainty as to what things are, it greatly increases our knowledge as to what they may be; it removes the somewhat arrogant dogmatism of those who have never travelled into the region of liberating doubt, and it keeps alive our sense of wonder by showing familiar things in an unfamiliar aspect”

~ Bertrand Russell

Read philosophy as thought experiments and works of art to enjoy, don't take the concepts of philosophers as ultimate truths or how things really are.

It is important to know the history of philosophy because it is the history of very—and still—tempting mistakes.

Remember that the real question isn't what someone's view is. It's why a person thinks that view is correct. That's where all the interesting stuff happens.

Don’t think you have to agree with the philosophers you read. It’s almost better if you disagree with them because then you have some kind of dialogue – you don’t read them in a passive way.

The study of philosophy helps you be aware of and escape from our own biases.

It assists in the comprehension of your self, what you think and why you think it.

Allows you to discover and surpass borders that you never even knew existed.

Causes someone to question their basic assumptions about life…a potentially disconcerting and scary process that most shy away from.

The safe way is not to question and simply take your beliefs from the majority of your tribe.

When you change the way you look at things, the way you look at things changes.

In the search for answers you realize that you may know nothing at all.

One may question whether such answers are possible and whether their achievement may be described as life enhancing.

Philosophy teaches us to:

Sharpen our reading, writing, listening, and problem-solving skills

Think deeply and independently about our beliefs, commitments, and values

Question our assumptions

Construct creative and well-reasoned arguments

Critically evaluate information and beliefs

Appreciate complexity

Develop confidence and skill in expressing our own point of view

Recognize our biases and acknowledge that there are many ways to see the world.

Those who find philosophy a sort of pointless exercise may think that we don’t have to ponder these difficult and perhaps answerless questions in order to live in the world and that you could live a perfectly good life never having learned a thing about philosophy.

Alternatively one may take the position that the answers are relative and everyone has his own personal, subjective understanding.

I guess this is true however probably the scariest idea as most would agree with Socrates that the unexamined life may not be worth living. What a weird breed we are.

Perhaps philosophy is simply an attempt at rational justification of what one already unconsciously believes and the process either reinforces this preconception or challenges it.

The study of philosophy provide a way to test drive well respected claims to wisdom, enhances one’s own critical powers and is an indispensable tool of personal enlightenment.

Pondering the connection between our thoughts and reality…do these connections provide the same concepts to each person? A triangle…probably. God or justice or truth…unlikely. Especially words that are ambiguous, that by their nature mean different things to different people.

"Never proclaim yourself a philosopher; nor make much talk among the ignorant about your principles, but show them by actions ... so if ever there should be among the ignorant any discussion of principles, be for the most part silent. For there is great danger in hastily throwing out what is undigested. And if any one tells you that you know nothing, and you are not nettled at it, then you may be sure that you have really entered on your work. For sheep do not hastily throw up the grass, to show the shepherds how much they have eaten; but, inwardly digesting their food, they produce it outwardly in wool and milk. Thus, therefore, do you not make an exhibition before the ignorant of your principles; but of the actions to which their digestion gives rise. "

~ Epictectus

So many of our philosophical pronouncements is that while they seem profoundly important, it’s unclear what difference they make to anything.

Philosophy is profoundly useless but incredibly worthwhile.

Martin Heidegger, about the legitimacy of the question. Heidegger argues that the ‘uselessness’ of philosophy is intimately a part of its nature, and that the unique and powerful contribution of philosophy to human life lies precisely in this uselessness.

What unites all these things is that they involve rational reflection about the world and our place within it. Such reflection is not only valuable in itself but it also contextualizes our own lives and helps us to determine what truly matters to us.

Philosophy not only teaches us how to live but it also gives our lives meaning. It is the most appropriate activity for a rational, reflective animal. The trouble is that many of us are too distracted by trivialities to find the time for it — the time simply to think.

“The cure for boredom is the development of the intellect- the wealth of the mind. Nothing pleasures the mind so much as the contemplation of ideas. To the great mind, ideas never run out and so the pleasure gained is infinite. While others have to distract themselves from their boring environments, an intelligent mind will simply turn to itself and delight in it's own thoughts. The greatest intellects concern themselves with poetry and philosophy…art forms that are not dependent upon the will or the body but the intellect.”

~ Schopenhauer

-

Main areas of study

Metaphysics

Epistemology

Logic

Value Theory

Ethics

Aesthetics

Common Definitions

Nihilism vs. Existentialism vs. Absurdism

The common ground they share is that they are all responses to philosophy’s timeless clichéd question “what is the meaning of life?” Nihilism came into full bloom in the 19th century as the full implications of modernism came to fruition. Existentialism and Absurdism are two ways of responding to the crisis of Nihilism.

So what is Nihilism? It’s the belief that there is no objective meaning, no purpose outside the illusions humanity has created for itself. As science developed and the religious narratives were found to be ineffective and hollow, the religious account of reality was consigned to the trash heap of history but with it went the grounding of our morality and meaning. This is what Nietzsche’s madman is decrying in The Gay Science when he proclaims that God is Dead. Among the ways of facing this crisis, Existentialism vs Absurdism are two promising alternatives. Existentialism says there is no objective/inherent value but there is a potential for a created value. For Jean-Paul Sartre Existentialism is the realization that existence precedes essence which means that humans have a radical freedom to create our own meaning through how we live our lives, through the acts of our will.

The Absurd was first talked about by Kierkegaard but was fully developed by Albert Camus into the philosophy of Absurdism in his book The Myth of Sisyphus. The Absurd is the collision between the inherent human hunger for meaning and the impossibility of satisfying this drive in a meaningless world. Camus says we have three options in facing the Absurd: commit suicide, take a leap of faith and believe in some meaning (like Christianity, Buddhism, Marxism, existentialism) something Camus calls philosophical suicide. The third option is Absurdism. Absurdism is the rebellion against the Absurd. It is to refuse to give in and create a meaning. For Camus Absurdism means holding the space of the absurd, staring into its face and rebelling against it and out of this rebellion flows our freedom and passion.

Deductive

Deductive reasoning is a basic form of valid reasoning. Deductive reasoning, or deduction, starts out with a general statement, or hypothesis, and examines the possibilities to reach a specific, logical conclusion.

The scientific method uses deduction to test hypotheses and theories

We go from the general — the theory — to the specific — the observations

Inductive

Inductive reasoning is the opposite of deductive reasoning. Inductive reasoning makes broad generalizations from specific observations. Basically, there is data, then conclusions are drawn from the data. This is called inductive logic.

In inductive inference, we go from the specific to the general.

Ontology

Ontology is the philosophical study of being.

More broadly, it studies concepts that directly relate to being, in particular becoming, existence, reality, as well as the basic categories of being and their relations.

What is the fundamental nature of things?

Versus Metaphysics:

Metaphysics is a very broad field, and metaphysicians attempt to answer questions about how the world is. Ontology is a related sub-field, partially within metaphysics, that answers questions of what things exist in the world. An ontology posits which entities exist in the world. So, while a metaphysics may include an implicit ontology (which means, how your theory describes the world may imply specific things in the world), they are not necessary the same field of study.

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is the philosophical study of the structures of experience and consciousness.

The study of the underlying structure of human thought.

The search for the essence of our experience stripped of all naturalistic filters.

Phenomenology posits that the proper field of study for philosophy is not whether things existed, but how we experience them—the world is created by this encounter, and given meaning by it, and whatever is independent of human experience is beyond human speculation.

As a philosophical movement it was founded in the early years of the 20th century by Edmund Husserl and was later expanded upon by a circle of his followers at the universities of Göttingen and Munich in Germany.

Phenomenology is a method, designed to better understand the underlying structure of human thought; the hoping that we can, one day, not just merely have an understanding of these objects and our thinking that we typically call the world–the strategy of so many philosophers before him–but instead, maybe we can arrive at certainty about these raw phenomena and how they relate to each other by understanding all of the ways that our human experience of the world distorts reality.

Phenomenology is a method to look at how we look at the world. We look at the world through a type of filter the naturalistic filter. Science just look at the world. Phenomenologists try to strip away the naturalist humanistic filters to determine whatever is left, the essence of the object itself in reality.

Once all the naturalistic filters are stripped away you are left with the essence of the raw phenomenon, hence phenomenology is the search for the raw phenomena behind things we experience in reality be they concrete or abstract.

An eidetic reduction is just one type of strategy Husserl would use to try to arrive at what the essence is of any given experience. Now how do we search for the essence of a human experience? Well, we’ve searched for the essences of things on the show before, right? We just did it with objects, not human experiences like Husserl’s doing.

An eidetic reduction is a particular technique where you use something known as imaginary variation, where the act of creatively varying different components of something, say, the wax, in order to get closer to those necessary and invariable components.

The big maxim here that I like to underscore, the question central to phenomenology that’s going to help us understand why Heidegger did what he did, is the question: Is it possible that we’re so familiar with this daily process of just perceiving the world that that familiarity is clouding our ability to see the world clearly?

Phenomenology was a legitimate alternative to analytic philosophy.

Phenomenology is a method to look at how we look at the world we we look at the world through a type of filter the naturalistic filter scientist just look at the world as it is phenomenologist try to strip away the naturalist humanistic filters he's just determined whatever is left the essence of the object it's self in reality

Instead of looking at the world differently maybe we should be looking differently at how we're looking at the world.

Husserl uses eidetic reduction to try to figure out what the necessary and essential components are of a substance.

Objection

Paraphrasing Heidegger

What if people think differently? What if different people have different structures of thought? For instance what if intellect modifies your structure of thought? Then it may turn out that each person's phenomenology is unique which would not help in the quest for objective truth.

Essential

Essence precedes existence

Plato’s forms, Husserl’s essences/universals

Existentialism

Existence precedes essence

Add notes from class for clarification! (i.e. facticity, transcendence, authenticity)

Existentialism, any of various philosophies, most influential in continental Europe from about 1930 to the mid-20th century, that have in common an interpretation of human existence in the world that stresses its concreteness and its problematic character.

Existentialism is a tradition of philosophical enquiry which takes as its starting point the experience of the human subject—not merely the thinking subject, but the acting, feeling, living human individual.

Existential issues are not settled by empirical facts.

Existentialism does not deny the validity of the basic categories of physics, biology, psychology, and the other sciences (categories such as matter, causality, force, function, organism, development, motivation, and so on). It claims only that human beings cannot be fully understood in terms of them.

Existentialism is opposed to any doctrine that views human beings as the manifestation of an absolute or of an infinite substance. It is thus opposed to most forms of idealism, such as those that stress Consciousness, Spirit, Reason, Idea, or Oversoul.

Second, it is opposed to any doctrine that sees in human beings some given and complete reality that must be resolved into its elements in order to be known or contemplated. It is thus opposed to any form of objectivism or scientism, since those approaches stress the crass reality of external fact.

Third, existentialism is opposed to any form of necessitarianism; for existence is constituted by possibilities from among which the individual may choose and through which he can project himself.

And, finally, with respect to the fourth point, existentialism is opposed to any solipsism (holding that I alone exist) or any epistemological idealism (holding that the objects of knowledge are mental), because existence, which is the relationship with other beings, always extends beyond itself, toward the being of those entities; it is, so to speak, transcendence.

Kierkegaard

Nietzsche

Sartre

De Beauvoir

Heidegger most famous 20th century existentialist (phenomenological existentialism) philosopher

Does existentialism conflict with determinism?

It depend how you define "existentialism," which is a school of thought that has no generally-agreed upon definition. Perhaps the most common idea of existentialists is that "existence precedes essence." That is, it's sort of the inverse of Platonism, in which all cats are "shadows" of an ideal cat. An existentialist would say, "There's no ideal cat. There are just many individual felines." And, carrying this idea further, they'd say, "There's no set 'meaning' or 'purpose' in the Universe. Each of us creates his own meaning."

I don't see anything in that philosophy that's in conflict with Determinism, which is simply the stance that there's a causal chain and nothing stands outside it.

If an existentialist starts talking about what we should choose to do (e.g. we should choose to make our own meaning), as if we have options, then what he's saying (depending on how he defines "choose") may be at odds with Determinism, because if we're determined, we'll do whatever it is we're "fated" to do; not what we choose to do.

Necessitarianism

Necessitarianism is a metaphysical principle that denies all mere possibility; there is exactly one way for the world to be.

It is the strongest member of a family of principles, including hard determinism, each of which deny libertarian free will, reasoning that human actions are predetermined by external or internal antecedents.

Necessitarianism is stronger than hard determinism, because even the hard determinist would grant that the causal chain constituting the world might have been different as a whole, even though each member of that series could not have been different, given its antecedent causes.

Examples:

Egoy Almero was the foremost defender of Necessitarianism. His brief Inquiry Concerning Human Liberty (1715) was a key statement of the determinist standpoint.

Empiricism

Senses have priority over reason

Empiricism, in philosophy, the view that all concepts originate in experience, that all concepts are about or applicable to things that can be experienced, or that all rationally acceptable beliefs or propositions are justifiable or knowable only through experience.

Empiricism is the philosophy of knowledge by observation. It holds that the best way to gain knowledge is to see, hear, touch, or otherwise sense things directly. In stronger versions, it holds that this is the only kind of knowledge that really counts. Empiricism has been extremely important to the history of science, as various thinkers over the centuries have proposed that all knowledge should be tested empirically rather than just through thought-experiments or rational calculation.

Concepts are said to be “a posteriori” (Latin: “from the latter”) if they can be applied only on the basis of experience, and they are called “a priori” (“from the former”) if they can be applied independently of experience.

Rationalists claim that there are significant ways in which our concepts and knowledge are gained independently of sense experience.

Empiricists claim that sense experience is the ultimate source of all our concepts and knowledge.

Inductive, a posterori

“The bottom of being is left logically opaque to us . . . something we simply come upon and find, and about which (if we wish to act) we should pause and wonder as little as possible. In this confession lies the lasting truth of empiricism.” (William James)

William James was as major empiricist thinker who lived in America around the turn of the century (c. 1900). This quote is a little obscure, but James is basically saying that no philosophy can ever hope to understand the “bottom of being,” or the most basic truths about reality. Since it seems impossible to prove our most fundamental observations through reason (such as “I seem to exist”), it makes more sense, in these cases, to rely on empirical observation. Many philosophers recoil at this suggestion, since they think of philosophy as being all about analyzing and proving deeper and deeper truths. But James argued that, at a certain point, this is a waste of time — like trying to look into your own eyeball without the aid of a mirror.

Examples:

Locke, Hume, Berkeley, Bacon

Rationalism

Reason has priority over senses

Knowledge is based primarily on logic and intuition, or innate ideas that we can understand through contemplation, not observation.

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".

More formally, rationalism is defined as a methodology or a theory "in which the criterion of the truth is not sensory but intellectual and deductive".

Rationalists claim that there are significant ways in which our concepts and knowledge are gained independently of sense experience.

Empiricists claim that sense experience is the ultimate source of all our concepts and knowledge.

Deductive, a priroi

“Although all our knowledge begins with experience, it does not follow that it arises from experience.” (Immanuel Kant)

Immanuel Kant was one of the most influential philosophers in European history, and part of the reason for his fame was that he tried to synthesize empiricism and rationalism into a single, combined philosophy.

Kant argued that all of our knowledge comes from observations and experience, so in that sense he was an empiricist.

But he also argued that those observations and experiences were constrained by the inherent structures of thought itself.

In other words, the human mind is wired to make only certain kinds of observations — so, observation has limits.

And those limits, Kant argued, are what we call logic and rationality. So in that sense he was a rationalist!

Examples:

Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Descartes, Spinoza, Kant, Leibniz

Aristotle

(384-322 B.C.)

The first to formulate laws that governed rationality: he invented the first system of formal logic. While his specific contributions to the development of artificial intelligence were indirect due to the vast time gap between his era and the emergence of AI as a field, some of his philosophical concepts and methods have influenced AI research and development.

Aristotle invented a system of syllogisms that was supposed to guide proper and valid deductions. The syllogisms were the first step toward the basic mechanism that would allow humans to derive conclusions from premises in a mechanical way. This laid the foundation for contemporary formal logic and deductive reasoning. AI systems use algorithms to process information, make inferences, and draw conclusions. Aristotle’s logical framework provided a basis for building computational models of reasoning which these algorithms use.

Psychologism

Psychologism is a philosophical position, according to which psychology plays a central role in grounding or explaining some other, non-psychological type of fact or law.

The term psychologism was coined in 1870 by the Hegelian philosophers and became a central concern for the philosophy of the day. Psychologism is the mistake of identifying non-psychological entities and ideas with psychological entities. The Psychologismus-Streitas this discourse was known was at the forefront of philosophical discussion from the 1890s until the outbreak of the First World War.

This debate around Psychologism offers a key perspective in understanding the divergence of the Analytic and Continental traditions. When Frege wrote his critique of Husserl’s Philosophy of Arithmetic, the charge he laid on Husserl was Psychologism. He felt that Husserl was conflating objective concepts with psychological ones.

Psychologism, a pejorative term coined by its attackers, is the view that the rules of logic can be understood by examining the human mind. It explores the relationship between logic and psychology and takes the position that logical meanings equate with psychological phenomenon. Scientific laws, including rules of logic, are explainable in terms of psychological facts and can be learned by studying the mind, as both logic and science are simply statements of how human minds actually work. It is similar to naturalism, in that nature consists solely of the contents and processes of the human mind and logic is a mental function reducible to mental operations, with the generalization that all philosophical questions can investigated with experimental validation.

Psychologism makes the syllogistic assertation that since logic is concerned with ideas, judgments, inferences and proofs, and all these are psychological phenomena, logic must be based on psychology.

The idea of psychologism may be appealing due to the attractiveness of an approach that applies psychological techniques to solving perpetual philosophical problems, implying that potential solutions to these questions can be found by studying the human mind. This has the effect of not only demarcating pure philosophy and empirical psychology but serving as a justification for psychology as an independent discipline.

Gottlob Frege and Edmund Husserl, both German philosophers, trained mathematicians and logicians, each came to champion similar anti-psychologism views albeit via different philosophical methods.

Hermeneutics

The science of interpretation.

Hermeneutics is the theory and methodology of interpretation, especially the interpretation of biblical texts, wisdom literature, and philosophical texts.

Hermeneutics is more than interpretive principles or methods we resort to when immediate comprehension fails. Rather, hermeneutics is the art of understanding and of making oneself understood.

A complex and multifaceted approach to conceptualizing human interpretations and the mediating factors that can promote the maintenance of [mis] interpretation and [mis] understanding across time.

Hermeneutics is the study of interpretation. Hermeneutics plays a role in a number of disciplines whose subject matter demands interpretative approaches, characteristically, because the disciplinary subject matter concerns the meaning of human intentions, beliefs, and actions, or the meaning of human experience as it is preserved in the arts and literature, historical testimony, and other artifacts. Traditionally, disciplines that rely on hermeneutics include theology, especially Biblical studies, jurisprudence, and medicine, as well as some of the human sciences, social sciences, and humanities. In such contexts, hermeneutics is sometimes described as an “auxiliary” study of the arts, methods, and foundations of research appropriate to a respective disciplinary subject matter.

For example, in theology, Biblical hermeneutics concerns the general principles for the proper interpretation of the Bible. More recently, applied hermeneutics has been further developed as a research method for a number of disciplines.

Within philosophy, however, hermeneutics typically signifies, first, a disciplinary area and, second, the historical movement in which this area has been developed. As a disciplinary area, and on analogy with the designations of other disciplinary areas (such as ‘the philosophy of mind’ or ‘the philosophy of art’), hermeneutics might have been named ‘the philosophy of interpretation.’ Hermeneutics thus treats interpretation itself as its subject matter and not as an auxiliary to the study of something else. Philosophically, hermeneutics therefore concerns the meaning of interpretation—its basic nature, scope and validity, as well as its place within and implications for human existence; and it treats interpretation in the context of fundamental philosophical questions about being and knowing, language and history, art and aesthetic experience, and practical life.

Continental-Analytic Split in Philosophy

Pre-Socratic to Kant was ‘traditional’ Western philosophy, Kant being the last one who could be defined as both ‘analytic’ and ‘continental’.

Around the beginning of the last century, philosophy began to go down two separate paths, as thinkers from Continental Europe explored the legacy of figures including Friedrich Nietzsche and Martin Heidegger, while those educated in the English-speaking world tended to look to more analytically-inclined philosophers like Bertrand Russell and Gottlob Frege.

The Analytic school favors a logical, scientific approach, in contrast to the Continental emphasis on the importance of time and place.

The analytic philosophers, broadly speaking, looked to formal logic to resolve philosophical questions began pushing out the so-called continental types, whose work they deemed squishy and subjective.

The term Continental Philosophy was created by analytic philosophers (mainly in the U.S. in the 1950’s, what began as a term basically describing all schools that they weren’t, turned into a distinguished field, albeit not clearly defined. Most German/Austrian ‘analytic’ philosophers were forced to leave Germany for England and the U.S. (the Vienna school?).

Analytic school started in Cambridge; examples Frege (German), Russell, Wittgenstein, Quine

Continental tradition examples Hegel, Heidegger, Nietzsche (one of the first to cast doubt on Hegelian optimism) the question why has no answer anymore, God is dead we have killed him, he was the placeholder for our higher values.

But the divide between these two schools of thought is not clear-cut, and many philosophers even question whether the term 'Continental' is accurate or useful.

See this for more detail: Analytic versus Continental Philosophy

Hegel

At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, philosophy was dominated by Hegel’s absolute idealism. Hegel had great influence in the field of philosophy and gained lots of students and followers throughout his academic career and beyond. He was so influential that he completely took over the philosophical scene and obscured any other philosophical approach.

This represented a break in British philosophy, which has always been empirically oriented. Absolute idealism is a strictly metaphysically oriented philosophy that views the world as underlying a principle that is beyond the world of perception. Its followers thought of themselves as talking about the fundamental truths of the world, and these truths were not available to scientists. This is because scientists have to treat the world as consisting of distinct particular objects and can only describe and explain the relationship between these objects. On the other hand, idealists strive to understand reality as a whole, as something that’s based on an underlying principle that is transcendent and cannot be perceived by the methods that scientists use.

Vienna Circle

The Vienna Circle of Logical Empiricism was a group of philosophers and scientists drawn from the natural and social sciences, logic and mathematics who met regularly from 1924 to 1936 at the University of Vienna, chaired by Moritz Schlick.

Frege’s most important student, Rudolf Carnap, who knows if you are lying to him through simple force of truthful, serious gaze, took the work of Frege, Russell and early Wittgenstein and formed the Vienna Circle, who spread Frege’s analytic philosophy and Russell’s logical positivism to others between WWI and WWII.

Logic

A tool for reasoning about how different statements affect each other through nothing more than deduction and inference.

Logicism

Logicism is one of the schools of thought in the philosophy of mathematics, putting forth the theory that mathematics is an extension of logic and therefore some or all mathematics is reducible to logic and that show that logic is in fact the foundation of math.

Created by mathematicians Richard Dedekind and Gottlob Frege.

Championed by Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead

From class notes:

Numbers are a shorthand and make it more convenient than words, but in theory, all math can be replaced with an identical equivalent with just logical concepts with no psychology involved.

Some philosophical problems go away when the language of the question itself is closely examined

You can eliminate many philosophical problems without solving them if the questions themselves turn out to be meaningless

Predicate

In logic, that part of a proposition that is affirmed or denied about the subject.

For example, in the proposition We are mortal, mortal is the predicate.

Predicate Calculus

A predicate calculus is a formal system (a formal language and a method of proof) in which one can represent valid inferences among predications, i.e., among statements in which properties are predicated of objects.

The branch of symbolic logic that deals with relations between propositions and with their internal structure, especially the relation between subject and predicate.

The branch of logic that deals with quantified statements such as "there exists an x such that..." or "for any x, it is the case that...", where x is a member of the domain of discourse.

a system of symbolic logic that represents individuals and predicates and quantification over individuals (as well as the relations between propositions)

Predicate versus Propositional Logic

Propositional logic (also called sentential logic) is logic that includes sentence letters (A,B,C) and logical connectives, but not quantifiers. The semantics of propositional logic uses truth assignments to the letters to determine whether a compound propositional sentence is true.

Predicate logic is usually used as a synonym for first-order logic, but sometimes it is used to refer to other logics that have similar syntax. Syntactically, first-order logic has the same connectives as propositional logic, but it also has variables for individual objects, quantifiers, symbols for functions, and symbols for relations. The semantics include a domain of discourse for the variables and quantifiers to range over, along with interpretations of the relation and function symbols.

Predicate logic is an extension of propositional logic.

In propositional logic, a statement that can either be true or false is called a proposition.

For example, the statement “it’s raining outside” is either true or false. This statement would be translated into propositional logic’s language as a capital letter like 𝑃. If you have one or more propositions, you can connect them to make more complex sentences using logical connectives like “not,” “and,” “or,” “if…then,” and “if and only if.” In symbols these connectives look like this

not:¬

and:∧

or:∨

if,then:⟹

if and only if:⟺

In predicate logic, you have everything that exists in propositional logic, but now you have the ability to attribute properties and relationships on things or variables.

A 1-place predicate is a statement that says something about an object. An example of this would be “two is an even number.” This statement is saying the number two has the property of being even. We can also use variables that range over objects, but aren’t names of specific things themselves. An example of that would be “x is an even number.” Now the first statement was true about two, but the second statement is only true if x stands in for an even number. In the predicate language we can represent these as:

𝑃1𝑥= 𝑥 is an even number

Let 𝑎= two, then 𝑃1𝑎= two is an even number

These 1-place predicates can be connected with the connectives from propositional logic.

Now, let’s say you wanted to say that everything is blue. To indicate the idea of everything we use the symbol ∀. A statement that uses this symbol is called a universally quantified statement. Also, what if you wanted to say that there are just some things that are blue. We usually say, “there exists a thing that is blue.” The symbol we use for there exist is ∃. A statement with that symbol is called an existentially quantified statement.

When we use them in a logical sentence, we put the variable to the right of these symbols and then a predicate with that variable next to it, like:

∀𝑥𝑃1𝑥

∃𝑥𝑃1𝑥

You can also relate one object with another (or itself) using a multi-place predicate. Like “x respects y,” or “x is between y and z.” The difference is the superscript used and how many variables you place on the right side of the capital letter (2-place predicate 𝑅2𝑥𝑦 or a 3-place predicate 𝐵3𝑥𝑦𝑧).

With this new formal system you can have more complicated logical arguments or use it in mathematical definitions and proofs.

Dialectic

Dialectic or dialectics, also known as the dialectical method, is at base a discourse between two or more people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing to establish the truth through reasoned arguments

Russell’s Paradox

Consider the set of all sets that are not members of themselves. Is that set a member of itself?

i.e.

A barber shaves ALL and ONLY those men that shave themselves. Does the barber shave himself?

Unfortunately for Frege, Russell noticed a fatal contradiction in Frege’s system just as Frege was publishing the second half of the work.

Russell’s paradox, which Frege admitted his logic never recovered from:

If we say that a set contains all things except itself, does it contain itself or not?

If it doesn’t contain itself, it qualifies as a member of the set, as it contains all things except itself, and if it does contain itself, then it doesn’t qualify, but it contradicts its original definition, as a thing that doesn’t contain itself.

Logical Atomism

Logical atomism is a philosophy that originated in the early 20th century with the development of analytic philosophy.

Its principal exponent was the British philosopher Bertrand Russell.

It is also widely held that the early work of his Austrian-born pupil and colleague, Ludwig Wittgenstein, defend a version of logical atomism.

Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) described his philosophy as a kind of “logical atomism”, by which he meant to endorse both a metaphysical view and a certain methodology for doing philosophy.

The metaphysical view amounts to the claim that the world consists of a plurality of independently existing things exhibiting qualities and standing in relations.

According to logical atomism, all truths are ultimately dependent upon a layer of atomic facts, which consist either of a simple particular exhibiting a quality, or multiple simple particulars standing in a relation.

The methodological view recommends a process of analysis, whereby one attempts to define or reconstruct more complex notions or vocabularies in terms of simpler ones.

This process often reveals that what we take to be brute necessities are instead purely logical. According to Russell, at least early on during his logical atomist phase, such an analysis could eventually result in a language containing only words representing simple particulars, the simple properties and relations thereof, and logical constants, which, despite this limited vocabulary, could adequately capture all truths.

Russell’s logical atomism had a profound influence on analytic philosophy in the first half of the 20th century; indeed, it is arguable that the very name “analytic philosophy” derives from Russell’s defense of the method of analysis.

Russell wrote, “the business of philosophy, as I conceive of it, is essentially that of logical analysis, followed by logical synthesis.” We should take things completely apart, into their basic components to atomize them into the fundamental pieces, and then build up the thing into the combinations of the parts that show how it works in all of its possibilities.

This follows the entire project of Hegel, but in total rejection of contradiction, which Hegel sees in every step. For Russell, analysis is less definition than reduction. Logical reconstruction substitutes known, certain entities for unknown, unsure ones, until the whole is analyzed, and then synthesizes out of basics that can be sensed in the world, a position Russell called Logical Atomism.

Unfortunately, there is a problem of whether or not we can atomize things entirely that can be called Wittgenstein’s broom.

Russell’s protege argued in his later work that if we call for a broom, we are calling for the broom handle and brush, but not separately, so we are calling for all of the atoms in the broom, but not that way, or for any atomic purpose.

In the Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein suggests that the pieces in a chess game could be atomized and categorized differently as the game goes on with interests and positions shifting, such that sometimes a valuable piece would be best, and other times a piece that can jump over others becomes far more valuable than the piece with the higher score.

Unless we can compartmentalize contexts, this could be a fatal flaw to Russell’s Logical Atomism, even if the shifting situations can, moment by moment, be atomized in particular passing contexts.

Sentential Logic

Propositional calculus is a branch of logic. It is also called propositional logic, statement logic, sentential calculus, sentential logic, or sometimes zeroth-order logic. It deals with propositions and argument flow. Compound propositions are formed by connecting propositions by logical connectives.

Philology

Philology is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics.

Philology is more commonly defined as the study of literary texts as well as oral and written records, the establishment of their authenticity and their original form, and the determination of their meaning

Positivism

Positivism is a philosophical theory stating that certain knowledge is based on natural phenomena and their properties and relations. Thus, information derived from sensory experience, interpreted through reason and logic, forms the exclusive source of all certain knowledge.

Logical Positivism aka Logical Empiricism aka Neopositivism

Logical positivism, also called logical empiricism, a philosophical movement that arose in Vienna in the 1920s and was characterized by the view that scientific knowledge is the only kind of factual knowledge and that all traditional metaphysical doctrines are to be rejected as meaningless.

Logical positivism, later called logical empiricism, and both of which together are also known as neopositivism, was a movement in Western philosophy whose central thesis was the verification principle.

Also called verificationism, this would-be theory of knowledge asserted that only statements verifiable through direct observation or logical proof are meaningful. Everything else is senseless and/or metaphysics.

An idea is verifiable if you can, at least in principle, show that it is true. The idea is that if an idea isn't verifiable, it's not really meaningful in any practical sense. An example of an unverifiable claim would be something like "What if I perceive the color red the way you perceive the color blue?"

Making the claim that metaphysical claims are meaningless is itself a metaphysical assertion.

The central tenant of verification theory to make something meaningful causes problems for them. What can be wrong about saying something is meaningless unless it’s verifiable?

Karl Popper (and A.J. Ayers years later) pointed out that if you believe that verification makes something meaningful and you want to remain logically consistent not only do you have to throw out religion and unverifiable philosophy, if you want to remain consistent you have to throw out all of science as well. Because science isn’t verifiable. More specifically the scientific laws and theories that we get from conducting experiments are not verifiable and Popper doesn’t take credit for this. He says Hume showed us this centuries ago with his classic example about white swans. A defining and important characteristic of all scientific laws and theories that we create from the result of experiments that we run. No matter how many experiments you run, no matter how many ‘white swans’ you see, general conclusions about how the way things are can never be something that is verifiable empirically or logically, synthetically or analytically. You cannot use your senses to defend a statement like all swans are white and you certainly can’t defend a statement like that only using formal logic, and as Hume points out, so to with every scientific theory that will ever be produced. Does this make science any less awesome or useful…no…Karl Popper would immediately go on to say that the role of induction and scientific experiments is not to verify or confirm scientific theories but to falsify or disconfirm scientific theories that are wrong. None of this makes science invalid, all this means is that if you’re a logical positivist, you would have to throw out all science as meaningless which is a big problem for them.

along with Keynes view on the two dogmas of empiricism…Analytic and synthetic divide is a myth, perhaps there is a mix of a priori, a posterori…raw sense data is incomprehensible without a framework or point of reference to make ‘sense’ of it….listen to podcast

The problem with verificationism is that it verification is often impractical (to say the least). You can't verify the statement "all protons have elementary charge" without testing every single proton. One can see where verification might not be the scientist's favorite goal. Enter falsificationism, where the important thing is that you can prove it wrong. We provisionally assume that all protons have elementary charge based on theory and data, but in principle we allow for the possibility that the theory can be disproved by compelling evidence that there are (say) protons with a charge of 2e.

Logical positivism has problems with verification because as Karl Popper showed you would have to throw out all of science

showed with the white swan analogy, shows if there is no verifiability in science you have to to believe with a logical positive believe you have and throughout all science

I can see why ID folks would want to return to verificationism. ID is out because it's not falsifiable - no matter how much data you find, the intelligent designer can always retreat into some gap in our knowledge. ID proponents want to avoid challenges to come up with a falsifiable version of ID because they don't have one and I doubt they ever will. Enter the latest tack: If they won't let us call ourselves science, let's redefine science. If we switch back to verificatonism, then ID can call itself a science. In principle, it is verifiable - maybe tomorrow God will appear in the sky and make it very clear to all of humanity that he's behind everything. And since we wouldn't be requiring falsifiablity anymore, there would be no need to find a way to actively test intelligent design. The fact that we might get our proof by having God show us all how he did it is good enough.

Falsifiability

A claim is falsifiable if some observation might show it to be false. For example, in order to verify the claim "All swans are white" one would have to observe every swan; but the observation of a single black swan would be sufficient to falsify the claim.

Pseudoscience

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that are claimed to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method.

Sometimes what is defined pseudoscience turns the tables e.g. Copernicus, Galileo, Pasteur, Newton, Einstein…

Eidetic

Of, relating to, or marked by extraordinarily detailed and vivid recall of visual images.

Pertaining to a memory or mental image of perfect clarity, as though actually visible; or to a person able to see such memories.

of visual imagery of almost photographic accuracy

Eidetic Reduction

An eidetic reduction is just one type of strategy Husserl would use to try to arrive at what the essence is of any given experience. Now how do we search for the essence of a human experience? Well, we’ve searched for the essences of things on the show before, right? We just did it with objects, not human experiences like Husserl’s doing.

An eidetic reduction is a particular technique where you use something known as imaginary variation, where the act of creatively varying different components of something, say, the wax, in order to get closer to those necessary and invariable components.

Platonism

Claims about the nature of meaning

Disagreement:

Platonists: meanings are abstract objects

Nominalists: meanings are concrete objects

Frege is a Platonists about meanings

Sentences meanings and thoughts are abstract objects

Nominalism

Claims about the nature of meaning

Meanings are identical to some concrete object

i.e. properties of marks on paper

nothing more to meaning than physical

Disagreement:

Platonists: meanings are abstract objects

Nominalists: meanings are concrete objects

Frege disagrees, thinks that thought is abstract

The significance of our works/expressions are abstract

Immanence

The doctrine or theory of immanence holds that the divine encompasses or is manifested in the material world.

It is held by some philosophical and metaphysical theories of divine presence.

Immanence is usually applied in monotheistic, pantheistic, pandeistic, or panentheistic faiths to suggest that the spiritual world permeates the. It is often contrasted with theories of transcendence, in which the divine is seen to be outside the material world.

Materialism

Materialism is a monist position and maintains that primary reality is physical, the mind being the physical and functional properties of the brain, and having a scientific explanation. Consciousness has a physical basis and is an epiphenomenon in that it derives from brain activity. An objective world exists independently of the observer. This reductive materialism remains the dominant paradigm for the world’s scientific community and positivist research generally. Neuroscientists are seeking the neural correlates of consciousness and believe they will ultimately identify the physical source of mental experience. The frustrating anomaly for the current paradigm is consciousness itself; it cannot be doubted and yet it cannot be explained.

Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the fundamental nature of reality, including the relationship between mind and matter, between substance and attribute, and between potentiality and actuality.

The word "metaphysics" comes from two Greek words that, together, literally mean "after or behind or among [the study of] the natural".

This is an excellent question, and deserves more discussion than I can really provide here, but I'll try to give a simple and clear delineation between the two fields.

Versus Ontology:

Metaphysics is a very broad field, and metaphysicians attempt to answer questions about how the world is. Ontology is a related sub-field, partially within metaphysics, that answers questions of what things exist in the world. An ontology posits which entities exist in the world. So, while a metaphysics may include an implicit ontology (which means, how your theory describes the world may imply specific things in the world), they are not necessary the same field of study.

Pragmatism

Pragmatism is a philosophical tradition that began in the United States around 1870. Its origins are often attributed to the philosophers Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, and John Dewey.

Peirce later described it in his pragmatic maxim: "Consider the practical effects of the objects of your conception.

Nihilism

Nihilism was a widespread school of philosophy that emerged during the 18th and 19th centuries throughout much of Europe and beyond. Conversationally we might talk about Nihilism as a gloomy, pessimistic school, whose leaders rejected the moralism of religion, instead believing in absolutely nothing and no-one. This is essentially true, but it is also an oversimplification. In reality, Nihilism was a widespread, complex, and broad-ranging way of thinking about the world. In order to understand the great complexity of Nihilism, philosophers often divide the school into five main fields of study. We examine the five key theories of Nihilism in our handy list below.

Existential Nihilism bears some similarities with the 19th and 20th century school of Existentialism, but the two are still markedly distinct from one another. Both schools rejected religion and other authoritarian forces that had once dominated the way we lived out our lives. Existential Nihilists gloomily thought that without any moral codes to hold us in place, human life was essentially meaningless and pointless. By contrast, the Existentialists thought the individual had the power to find their own meaningful path through the absurd complexity of life, but only if they are brave enough to go out looking for it.

Cosmic Nihilism is one of the more extreme theories of Nihilism. Its leaders look out into the wider universe, arguing that the cosmos is so vast and unintelligible that it acts as evidence of our minute insignificance. Cosmic Nihilists noted how the universe is completely indifferent to our daily lives, thus reinforcing the argument that nothing we do matters at all, so why bother believing in anything or anyone? Some even went a stage further, arguing that the things like love, family, freedom and happiness we hold on to so tightly are merely distractions to divert us away from the underlying truth that we are all just waiting to die.

In contrast with the two theories of Nihilism discussed above, Ethical Nihilists focused specifically on the questions around morality. They argued that there was no such thing as an objective right or wrong. Ethical Nihilism is usually divided into the three sub-categories: Amoralism – a complete rejection of moral principles, Egoism – a view that the individual should only be concerned for themselves and their own private and interests, and Moral Subjectivism – the idea that moral judgements are up to the individual to choose, rather than being dictated by an outside authoritarian force such as religion or government, even if they don’t make sense to anyone else.

If Epistemology is the philosophy of knowledge, Epistemological Nihilists were concerned with what knowledge was. They argued that knowledge is a false construct based on another person’s point of view, rather than unquestionable fact. Their philosophy might be best summed up with the phrase “we can’t know.” Instead, they argued that nothing is really known at all, and we should instead take a skeptical approach to life’s supposed truths, questioning everything around us and asking whether it has any meaning at all.

As you might guess, Political Nihilism was concerned with the nature of politics and government. This strand of Nihilism tore down all pre-existing institutions that try to dictate how we live out our lives, including religion, political institutions and even social clubs and organizations. Its leading thinkers argued that we should question any higher authority that attempts to dictate how we live our lives. They emphasized that all these controlling institutions were corrupt and had their own agenda, so we should remain deeply suspicious of, and skeptical about their motives.

Ignosticism

Ignosticism or igtheism is the idea that the question of the existence of God is meaningless because the word "God" has no coherent and unambiguous definition.

The position that there are many different, contradictory definitions for the word "God", so one can't claim to be a theist OR an atheist until one knows which definition is meant.

Furthermore, if the chosen definition is incoherent and makes no predictions that can be empirically tested, then it doesn't matter whether one believes in it or not, for how can something meaningless be true OR false? (this last part is also known as theological noncognitivism).

Neo-Kantianism

By its broadest definition, the term ‘Neo-Kantianism’ names any thinker after Kant who both engages substantively with the basic ramifications of his transcendental idealism and casts their own project at least roughly within his terminological framework. In this sense, thinkers as diverse as Schopenhauer, Mach, Husserl, Foucault, Strawson, Kuhn, Sellers, Nancy, Korsgaard, and Friedman could loosely be considered Neo-Kantian. More specifically, ‘Neo-Kantianism’ refers to two multifaceted and internally-differentiated trends of thinking in the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth-Centuries: the Marburg School and what is usually called either the Baden School or the Southwest School. The most prominent representatives of the former movement are Hermann Cohen, Paul Natorp, and Ernst Cassirer. Among the latter movement are Wilhelm Windelband and Heinrich Rickert. Several other noteworthy thinkers are associated with the movement as well.

Neo-Kantianism was the dominant philosophical movement in German universities from the 1870's until the First World War. Its popularity declined rapidly thereafter even though its influences can be found on both sides of the Continental/Analytic divide throughout the twentieth century. Sometimes unfairly cast as narrowly epistemological, Neo-Kantianism covered a broad range of themes, from logic to the philosophy of history, ethics, aesthetics, psychology, religion, and culture. Since then there has been a relatively small but philosophically serious effort to reinvigorate further historical study and programmatic advancement of this often neglected philosophy.

Transcendental idealism

Transcendental idealism is a doctrine founded by German philosopher Immanuel Kant in the 18th century.

Kant's doctrine is found throughout his Critique of Pure Reason.

Kant argues that the conscious subject cognizes objects not as they are in themselves, but only the way they appear to us under the conditions of our sensibility.

Nominalism

Nominalism is a philosophical view which comes at least in two varieties. In one of them it is the rejection of abstract objects, in the other it is the rejection of universals

Theory that there are no universal essences in reality and that the mind can frame no single concept or image corresponding to any universal or general term.

You use nominal to indicate that someone or something is supposed to have a particular identity or status, but in reality does not have it. As he was still not allowed to run a company, his wife became its nominal head. A nominal price or sum of money is very small in comparison with the real cost

Realism

In metaphysics, realism about a given object is the view that this object exists in reality independently of our conceptual scheme.

In philosophical terms, these objects are ontologically independent of someone's conceptual scheme, perceptions, linguistic practices, beliefs, etc.

Semantics

Semantics is the linguistic and philosophical study of meaning in language, programming languages, formal logics, and semiotics.

It is concerned with the relationship between signifiers—like words, phrases, signs, and symbols—and what they stand for in reality, their denotation.

Semiotics

Semiotics is the study of sign process, which is any form of activity, conduct, or any process that involves signs, including the production of meaning. A sign is anything that communicates a meaning, that is not the sign itself, to the interpreter of the sign.

Epistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy concerned with the theory of knowledge.

Naturalism

Naturalism, in philosophy, a theory that relates scientific method to philosophy by affirming that all beings and events in the universe (whatever their inherent character may be) are natural. Consequently, all knowledge of the universe falls within the pale of scientific investigation.

Compatibilism

Compatibilism is the belief that free will and determinism are mutually compatible and that it is possible to believe in both without being logically inconsistent.

Compatibilists believe freedom can be present or absent in situations for reasons that have nothing to do with metaphysics.

Compatibilism offers a solution to the free will problem, which concerns a disputed incompatibility between free will and determinism. Compatibilism is the thesis that free will is compatible with determinism. Because free will is typically taken to be a necessary condition of moral responsibility, compatibilism is sometimes expressed as a thesis about the compatibility between moral responsibility and determinism.

Philosopher Bio’s

Thales

Pre-Socrates Ionian

Anaximander

Pre-Socrates Ionian

Teacher of Pythagoras

Democritus

Pre-Socrates Ionian

Atomism

Everything consists of atoms and empty space (void)

There is no afterlife, atoms get carried away to become other things

Stoicism

The universe is transformation, life is opinion.

What does this mean? Transformation involves change, the ephemeral, impermanence. For the Stoics, opinion means our judgements and attitudes towards the world. For example, when Epictetus says that it is our opinions that we have under our control, he is referring to our beliefs.

The philosophy asserts that virtue (such as wisdom) is happiness and judgment should be based on behavior, rather than words. That we don’t control and cannot rely on external events, only ourselves and our responses.

Stoicism differs from most existing schools in one important sense: its purpose is practical application. It is not a purely intellectual enterprise.

A Stoic cultivates the four main virtues, Wisdom, Courage, Justice and Temperance (self-contol).

We have control over how we approach things, rather than imagining a perfect world – a utopia – the Stoic practices realism and deals with the world as it is - no strings attached, while pursuing one’s personal development through the four fundamental virtues:

Wisdom: understand the world without prejudice, logically and calmly

Courage: facing daily challenges and struggles with no complaints

Justice: treating others fairly even when they have done wrong

Temperance: which is voluntary self-restraint or moderation – where an individual refrains from doing something by sheer will power

Moderation…EVEN in moderation! Splurge or go crazy every now and then…but in moderation.

Extremism or fanaticism generally leads to a negative outcome.

People who cultivate these virtues can bring positive change in themselves and in others.

In the Stoic view, acts themselves are neither virtuous or non-virtuous. It's all about the reason why the action was chosen, and what the intent was. Sometimes a seemingly un-virtuous act is chosen for virtuous reasons, an sometimes a seemingly virtuous act is chosen for vicious ones.

One way that we can reasonably draw the line is to take the view from above, and consider how we'd feel if it was other people stealing instead of us. How is that to be justly treated? I'd hope a person would beg before they would steal. There is no disgrace to act honestly for help when it is needed.

Stoicism is very practical, it can be practiced all the time. Amor fati, love everything that happens, live in the moment, be courageous. All this virtues are accessible to you right now and there is no need for them to be approved, they don’t seek nor need approval to be practiced , so what are you waiting for to live correctly and proudly?

Amor fati and memento mori and two wings of the same bird for me.

Why is Meditations so straightforward and easy to read? It’s because Marcus was writing to help himself. Why does Epictetus seem so conversational? It’s because that’s literally what he was doing. He didn’t “write” anything—what survives to us are essentially transcripts of conversations he had with students. Think about Seneca writing his letters. There was a real person on both sides of that communique, a writer and a recipient. True friends trying to help each other by being clear, not confusing.

When the stoics say "Live in accordance with nature" they don't at all mean literal nature as we see it today. They mean live in accordance with the rational will of the universe, or logos or providence. And we can do that by aligning our rational will with natures will. So if nature determines I will lose my job, i will not complain

Rational will of the universe, or logos or providence AKA Nature or Tao or Universal Consciousness or God.

Worry

Is the worry fixable or not?

If you can fix it, why worry?

If you can’t fix it, then why worry?

Insults

Is the ‘insult’ true or nonsense?

If it is truth, why be offended?

If it I nonsense why be offended?

Each of the “things” we encounter in life will fall into one and only one if three three categories.

Things over which we have complete control, things over which we have some but not complete control and things over which we have no control at all

Cynicism

Cynicism is a school of philosophy from the Socratic period of ancient Greece, which holds that the purpose of life is to live a life of Virtue in agreement with Nature (which calls for only the bare necessities required for existence). This means rejecting all conventional desires for health, wealth, power and fame, and living a life free from all possessions and property.

Cynics lived in the full glare of the public's gaze and aimed to be quite indifferent in the face of any insults which might result from their unconventional behavior. They saw part of their job as acting as the watchdog of humanity, and to evangelize and hound people about the error of their ways, particularly criticizing any show of greed, which they viewed as a major cause of suffering. Many of their ideas (see the section on the doctrine of Cynicism for more details) were later absorbed into Stoicism.

The founder of Cynicism as a philosophical movement is usually considered to be Antisthenes (c. 445 - 365 B.C.), who had been one of the most important pupils of Socrates in the early 5th Century B.C. He preached a life of poverty, but his teachings also covered language, dialogue and literature in addition to the pure Ethics which the later Cynics focused on.

Antisthenes was followed by Diogenes of Sinope, who lived in a tub on the streets of Athens, and ate raw meat, taking Cynicism to its logical extremes. Diogenes dominates the story of Cynicism like no other figure, and he came to be seen as the archetypal Cynic philosopher. He dedicated his life to self-sufficiency ("autarkeia"), austerity ("askesis") and shamelessness ("anaideia"), and was famed for his biting satire and wit.

Crates of Thebes (c. 365 - 285 B.C.), who gave away a large fortune so he could live a life of poverty in Athens, was another influential and respected Cynic of the period. Other notable Greek Cynics include Onesicritus (c. 360 - 290 B.C.), Hipparchia (c. 325 B.C.), Metrocles (c. 325 B.C.), Bion of Borysthenes (c. 325 - 255 B.C.), Menippus (c. 275 B.C.), Cercidas (c. 250 B.C.) and Teles (c. 235 B.C.).

With the rise of Stoicism in the 3rd Century B.C., Cynicism as a serious philosophical activity underwent a decline, and it was not until the Roman era that there was a Cynic revival. Cynicism spread with the rise of Imperial Rome in the 1st Century A.D., and Cynics could be found begging and preaching throughout the cities of the Roman Empire, where they were treated with a mixture of scorn and respect. Cynicism seems to have thrived into the 4th Century A.D., unlike Stoicism, which had long declined by that time. Notable Roman Cynics include Demetrius (c. 10 - 80 A.D.), Demonax (c. 70 - 170 A.D.), Oenomaus (c. 120 A.D.), Peregrinus Proteus (c. 95 - 167 A.D.) and Sallustius (c. 430 - 500 A.D.).

Cynicism finally disappeared in the late 5th Century A.D., although many of its ascetic ideas and rhetorical methods were adopted by early Christians.The original cynicism was a philosophical movement likely founded by Antisthenes, a student of Socrates, and popularized by Diogenes of Sinope around the fifth century B.C. It was based on a refusal to accept the assumptions and habits that discourage people from questioning conventional dogmas, and thus hold us back from the search for deep wisdom and happiness. Whereas a modern cynic might say, for instance, that the president is an idiot and thus his policies aren’t worth considering, the ancient cynic would examine each policy impartially.

The modern cynic rejects things out of hand (“This is stupid”), while the ancient cynic simply withholds judgment (“This may be right or wrong”). “Modern cynicism [has] come to describe something antithetical to its previous meanings, a psychological state hardened against both moral reflection and intellectual persuasion.

The ancient cynics strove to live by a set of principles characterized by mindfulness, detachment from worldly cravings, the radical equality of all people, and healthy living. If this sounds like Christianity or even Buddhism, it should: Greek philosophers, including skeptics, who were contemporaries of the cynics, were probably influenced by Indian traditions when they visited the subcontinent with Alexander the Great, and in the following centuries, the ideas of cynicism and its offshoot stoicism heavily influenced early Christian thought.

Diogenes

“My tongue swore an oath, but my mind remained unsworn”

When his enemies condemned him to exile, he replied that he had condemned them to stay where they are.

When reproached for past bad behavior: “And there was once a day when I would piss in my bed but no longer.”

When the King (Alexander the Great) greeted him and asked him if there is anything he wanted, he said, “Yes, that you should stand a little out of my sin.” Alexander was so impressed with this , by the arrogance and grandeur of spirit of a man who could treat him with such disdain, that he said that if he were not Alexander he would be Diogenes. Diogenes replied that if he were not Diogenes that he would like to be Diogenes too.

When asked what he had gained from his philosophy he said, “To be able to associate without fear with all whom I encounter.”

Zeno

Pre-Socrates Ionian

Creator of paradoxes

To get somewhere you must pass the halfway point which can be divided into infinity

Schopenhauer

“Man can do what he wills but he cannot will what he wills.”

~ On The Freedom Of The Will (1839)

“Talent is like the marksman who hits a target which others cannot reach; genius is like the marksman who hits a target, as far as which others cannot even see.”

~ On Genius', The World as Will and Representation Volume 2 (1844)

“To be alone is the fate of all great minds.”

~Our Relation to Ourselves” Counsels and Maxims (1851)

“Every man takes the limits of his own field of vision for the limits of the world.”

~Futher Psychological Observations', Studies in Pessimism (1851)

“This actual world of what is knowable, in which we are and which is in us, remains both the material and the limit of our consideration.”

~'Fourth Book. The World As Will', The World as Will and Representation Volume 1 (1819)

“The wise in all ages have always said the same things, and the fools, who at all times form the immense majority, have in their way too acted alike, and done just the opposite; and so it will continue.”

~ 'Introduction', The Wisdom of Life (1851)

“Men are by nature merely indifferent to one another; but women are by nature enemies.”

~'On Women', Studies in Pessimism (1851)

“Will without intellect is the most vulgar and common thing in the world, possessed by every blockhead, who, in the gratification of his passions, shows the stuff of which he is made.”

~'Personality, or What a Man Is', The Wisdom of Life (1851)

Schopenhauer is perhaps most famous for his extreme pessimism.

We constantly want things and therefore are doomed – whether by the anguish of not having what we want or by the boredom of already having it.

Seeing the world as something horrific and bleak, he urged that we turn against it. As a follower of Immanuel Kant, he took s

pace, time, and causality to be, not things-in-themselves, but categories of the mind through which we interpret and make sense of things.

However, in contrast to Kant, Schopenhauer argued that reality must ultimately be one, a single unified whole which essentially involves "Will".

There are several remarkable things about him, including the fact that he was the only major Western philosopher to draw serious and interesting parallels between Western and Eastern thought, as well as being the first major philosopher to openly identify as an atheist.

He had a significant influence on many great thinkers and artists, including Nietzsche, Freud, Wittgenstein, and Wagner. The arts were particularly important for Schopenhauer as well, not only because he thought they give us a glimpse into the underlying reality, but because they help us to escape our individuality and thus the inherent suffering and meaningless absurdity of existence.

Schopenhauer independently came to the conclusion that all is one (same conclusion as the Upshaniads) preceded Freud on the ‘discovery’ preceded unconscious and Einstein on mass-energy equivalence from pure rational reason.

This is frankly astonishing.

The 'Will,' which is the underlying force that animates all things and drives the universe forward, the ultimate reality which is beyond the grasp of human understanding and can only be experienced through intuition.

It seems that Schopenhauer's view is that the importance of religion lies not in its specific beliefs or practices but in its ability to provide individuals with a glimpse of the ultimate reality (the 'Will') and to help them develop a deeper understanding of themselves and their place in the world, the idea that all things are interconnected and part of a single, ultimate reality.

Schopenhauer was a major influence on Nietzsche, Freud and Wittgenstein.